Several weeks ago, I bought a yardlong picture at an antique shop. Finding a frame to fit the picture is next to impossible, so I knew I had to make one.

I looked around for some wood and found a piece of ash from a project I made a few years ago. Ash is not the ideal wood to use with molding planes as it has a lot of moving grain. Preferably poplar or mahagony would be the ideal wood, but ash is what I have.

I ran my complex molding plane over the board and slowly cut the profile in the wood. It took about 20-30 minutes for me to cut the profile.

I then took the board over to the table saw and ripped the molding 1″ wide.

I didn’t want the sides of the frame to be flat, so I carefully gouged out the middle, starting with carving gouge, then switched over to my No 6 hollow plane. Then I finished up with a piece of sand paper wrapped around a 1/2″ dowel.

I cut the rabbets for the frames on the table saw. I made three moldings that were longer than what I needed. I wasn’t concerned about the ends of the molding because I was going to cut them away anyway.

Using my Stanley No 150 Miter Box and my miter trimmer, I cut the piece out.

The molding pieces are now looking like a frame.

After I cut all the pieces, I dried fitted them together to see how the corners met. If they needed attention, I would carve and sand the ends to meet each other.

The final frame looks pretty good. Now it’s up to my wife, Anita, if she wants to stain or paint it.

This is the first time this year where I have had time to work in the shop, and it felt great. My job keeps me busy during the week, and the weekends are often antique hunting with Anita. I’m glad I had the time yesterday.

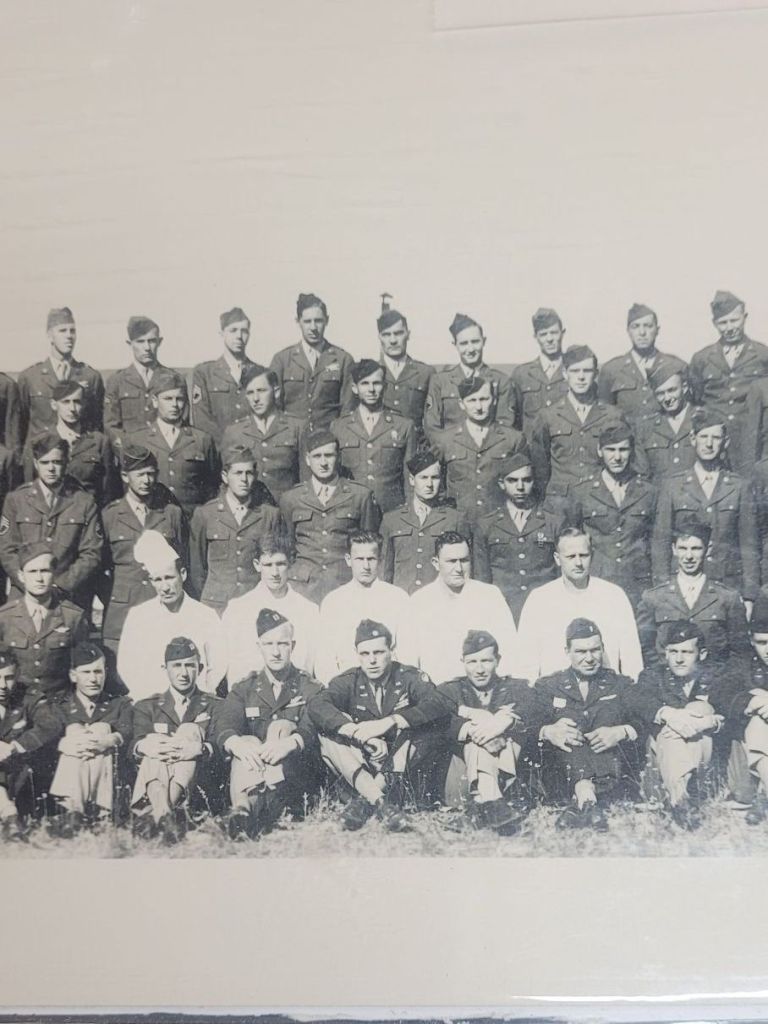

I’m not sure which branch of the military these men served or when the picture was taken, as there is no stamp on the picture, but they may have served in WWI as many of the yardlongs I’ve seen are early 20th century. All I know is that these men fought and may have died for our country, so they need to be honored by being put into a frame and hung on someone’s wall.

Happy Easter!